India’s digital payments ecosystem has evolved from a facilitator-led model to a systemically important financial infrastructure. As transaction volumes scale and intermediaries increasingly sit between payers and merchants, the regulatory lens has decisively shifted from technology enablement to funds custody and settlement risk. This shift is most visible in the regulatory treatment of “Payment Aggregators” and “Payment Gateways”, two terms often used interchangeably in commercial parlance, but fundamentally distinct in law.

Under the Reserve Bank of India’s Master Direction on Regulation of Payment Aggregators, 2025 (the “PA Master Directions”)[1], a “Payment Aggregator” or “PA” is an entity that facilitates the aggregation of payments from customers, temporarily handles such funds, and subsequently settles them to merchants through one or more payment channels. In contrast, a “Payment Gateway” or “PG” is expressly defined as a technology service provider that merely routes and processes payment instructions, without any involvement in the handling or settlement of funds.

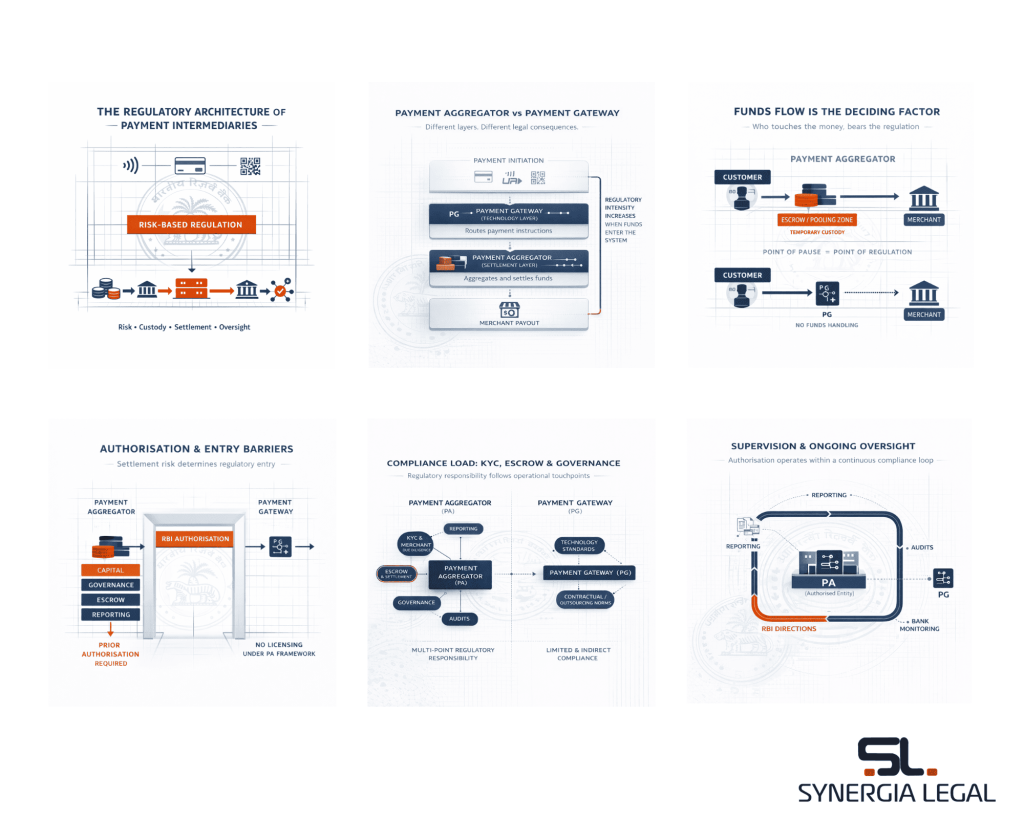

This distinction is not semantic. It determines whether an entity is required to obtain regulatory authorisation, maintain minimum net worth, comply with escrow and settlement restrictions, undertake merchant due diligence, and submit to continuous supervisory oversight by the RBI. The PA Master Directions, issued under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 and the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999, consolidate and overhaul India’s regulatory framework for payment intermediaries, covering domestic, physical, online, and cross-border payment aggregation under a unified regime.

This article examines the legal, structural, and operational differences between PAs and PGs, with a particular focus on how the RBI’s post-2025 framework redraws compliance boundaries based on who touches the money and when.

The RBI’s Regulatory Architecture for Payment Intermediaries

The Reserve Bank of India’s regulatory oversight over payment intermediaries is rooted in its statutory mandate under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 (“PSS Act”) and, where cross-border flows are involved, the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (“FEMA”). Exercising its powers under Section 18 read with Section 10(2) of the PSS Act, and Sections 10(4) and 11(1) of FEMA, the RBI has consistently approached payment regulation through a risk-based lens—placing heightened scrutiny on entities that handle, pool, or temporarily hold customer funds.

Historically, this oversight evolved in a fragmented manner. The Guidelines on Regulation of Payment Aggregators and Payment Gateways issued in 2020 and 2021 introduced the first formal regulatory distinction between “Payment Aggregators” and “Payment Gateways”. This was followed by a separate regulatory framework for “Payment Aggregators – Cross Border” in 2023, and draft directions in 2024 addressing physical point-of-sale aggregation and structural gaps in the existing regime. While these measures expanded regulatory coverage, they also resulted in definitional overlaps, transitional uncertainty, and scope for regulatory arbitrage across business models.

The PA Master Directions marks a decisive shift from this piecemeal approach to a consolidated and unified regulatory architecture. The PA Master Directions subsume and repeal the earlier guidelines, and comprehensively regulate “Payment Aggregators” across three categories i.e., “PA – Online”, “PA – Physical”, and “PA – Cross Border”, under a single framework governing authorisation, capital adequacy, governance, merchant due diligence, escrow arrangements, settlement discipline, and reporting obligations.

At the same time, the RBI has deliberately drawn a regulatory boundary by expressly excluding “Payment Gateways” from the scope of the PA Master Directions, recognising them as technology service providers that do not handle or settle funds. This architectural choice underscores the RBI’s central regulatory premise: where an entity touches customer money, regulatory intensity follows, a principle that frames the comparative analysis between PAs and PGs in the sections that follow.

Conceptual Difference: What Is a “Payment Aggregator” vs a “Payment Gateway”?

Any analysis of “Payment Aggregators” and “Payment Gateways” must begin with the definitions prescribed by the Reserve Bank of India under the PA Master Directions. A “Payment Aggregator” or “PA” is defined as an entity that facilitates the aggregation of payments made by customers to merchants through one or more payment channels and subsequently settles the collected funds to such merchants. Crucially, this definition expressly contemplates the handling of funds by the intermediary.

In contrast, a “Payment Gateway” or “PG” is defined as an entity that provides technology infrastructure to route and facilitate the processing of a payment transaction without any involvement in the handling of funds. The PA Master Directions further clarify that a PG does not fall within the scope of the regulatory framework applicable to PAs.

These definitions reflect materially different roles within the payment ecosystem. A PA sits within the transaction chain between the payer and the merchant. It receives customer payments, pools them in designated escrow accounts, and undertakes settlement to merchants in accordance with contractual timelines. Even where such custody is temporary, the PA assumes responsibility for settlement discipline, refunds, chargebacks, reconciliation, and merchant payouts.

A PG, by contrast, functions as a technological conduit. Its role is limited to securely transmitting payment instructions between the payer, issuing bank, card networks, and acquiring bank. At no stage does a PG receive, hold, or disburse customer funds.

The custody of funds is the conceptual fulcrum on which the PA–PG distinction rests. Once an entity touches customer money, it introduces settlement risk, consumer protection concerns, and systemic exposure. It is this risk profile that justifies the RBI’s regulatory focus on PAs.

The RBI’s framework adopts a substance-based approach. An entity labelled as a “PG” but operationally involved in settlement or funds pooling would be treated, in substance, as a “PA”. Labels yield to actual funds flow—a principle that underpins the regulatory architecture examined in the sections that follow.

Funds Flow as the Deciding Factor: Who Touches the Money?

At the heart of the RBI’s regulatory approach to payment intermediaries lies a simple but decisive question: who handles customer funds, and at what stage. The PA Master Directions reflect a risk-based philosophy under which regulatory intensity increases once an intermediary assumes custody, however temporary, of money belonging to customers or merchants. The movement, pooling, and settlement of funds are treated as inherently higher-risk activities, warranting closer supervisory oversight under the PSS Act and, where applicable, FEMA, 1999.

1. Funds Flow in a Payment Aggregator Model

In a typical “Payment Aggregator” structure, the PA sits directly within the payment value chain. Customer payments are routed through the PA and credited into a designated escrow account maintained with a scheduled commercial bank. These funds are temporarily pooled before being settled onward to merchants in accordance with agreed timelines. Even where settlement occurs on a near-real-time basis, the PA remains contractually and operationally responsible for fund reconciliation, refunds, chargebacks, and failed transactions.

It is this interposition of the PA between the payer and the merchant, coupled with custody of funds, that creates settlement risk and consumer exposure. The PA Master Directions respond to this risk by imposing escrow safeguards, governance standards, reporting obligations, and audit requirements on PAs.

2. Funds Flow in a Payment Gateway Model

A “Payment Gateway”, by contrast, is structurally excluded from the funds flow. A PG merely transmits payment instructions between the payer, issuing bank, card network, and acquiring bank. Customer funds move directly from the payer’s bank to the merchant’s bank through regulated banking and card network rails, without ever being received, held, or disbursed by the PG. Consequently, the PG does not assume settlement responsibility or introduce custody-related risk.

3. Regulatory Consequences of Touching the Money

This distinction in funds flow explains the RBI’s differential regulatory treatment. Entities that touch the money are required to obtain authorisation, maintain minimum net worth, comply with escrow and settlement discipline, and submit to continuous supervision. Entities that do not, such as PGs, are consciously kept outside the PA regulatory perimeter.

4. Substance Over Labels

The RBI assesses the fit and proper status of promoters, directors, and key managerial personnel, including their integrity, track record, and financial soundness. The regulator retains discretion to impose conditions or decline authorisation where governance concerns arise.

Authorisation & Entry Barriers: PA v. PG

Under the RBI’s payments framework, authorisation is not model-agnostic. It is triggered by the nature of activities undertaken, specifically, whether an intermediary handles or settles customer funds. Acting under the PSS Act, the RBI has made authorisation a prerequisite for entities whose operations introduce settlement and custody risk into the payments ecosystem. This approach aligns directly with the funds-flow logic discussed earlier: where an entity touches the money, regulatory permission follows.

1. Authorisation Framework for Payment Aggregators

All non-bank entities proposing to operate as “Payment Aggregators”—whether as “PA-Online”, “PA-Physical”, or “PA-Cross Border”—are required to obtain prior authorisation from the RBI. Such entities must be incorporated in India under the Companies Act, 2013, and their constitutional documents must expressly permit PA activity. Applications are to be submitted through the RBI’s online portal, and entities regulated by another financial sector regulator must additionally obtain a no-objection certificate from the relevant regulator.

Banks carrying on PA business are exempt from this authorisation requirement, reflecting the RBI’s confidence in the prudential oversight already applicable to banking entities.

2. Capital Adequacy as a Structural Entry Barrier

Authorisation as a PA is accompanied by meaningful capital thresholds. An applicant is required to have a minimum net worth of ₹15 crore at the time of application and to achieve a net worth of ₹25 crore within three financial years of authorisation, with ongoing maintenance thereafter. These thresholds underscore the RBI’s intent to permit only adequately capitalised entities to intermediate customer funds at scale.

3. Transitional Obligations and Wind-Down Risk

The PA Master Directions also prescribe strict transitional timelines. Entities already engaged in PA activities are required to apply for authorisation within stipulated deadlines, failing which they must wind down their operations. This framework leaves limited room for regulatory forbearance or informal continuation.

4. Payment Gateways: No Licence, But Not No Exposure

“Payment Gateways” are expressly excluded from the authorisation regime, as they do not handle funds. However, this absence of licensing should not be mistaken for regulatory irrelevance. PGs remain exposed through outsourcing arrangements, contractual dependencies with regulated PAs and banks, and recommended adoption of RBI-prescribed technology and cyber-security standards.

Governance, Conduct & Compliance Obligations

Once authorised, a “Payment Aggregator” is subject to a governance framework that treats it as a regulated financial intermediary rather than a neutral technology platform. The PA Master Directions mandate that a PA be professionally managed, with promoters and directors meeting prescribed fit and proper criteria relating to integrity, reputation, financial soundness, and absence of regulatory or criminal disqualifications. The RBI retains discretion to independently assess suitability and to seek inputs from other regulators and government authorities. Further, any change in control, management, or ownership of a non-bank PA requires prior RBI approval, underscoring governance continuity as a condition of authorisation.

1. Conduct Obligations and Merchant-Facing Discipline

The regulatory framework also imposes behavioural discipline on PAs in their dealings with merchants and ecosystem participants. PAs are required to clearly delineate roles and responsibilities across agreements with merchants, acquiring banks, and other stakeholders, covering refunds, failed transactions, reconciliation, and grievance handling. Importantly, a PA is prohibited from carrying on marketplace activity and may aggregate payments only for merchants with whom it has a direct contractual relationship. Pricing transparency, adherence to Merchant Discount Rate (“MDR”) instructions, and clear disclosure of charges form an integral part of this conduct framework.

2. Dispute Management and Consumer Protection

Consumer protection is addressed indirectly through mandatory dispute management obligations. Every PA must maintain a documented dispute resolution framework, aligned with RBI-prescribed turnaround times for failed transactions and refunds. This includes responding to chargebacks, assigning appropriate reason codes, and appointing a designated grievance officer with a publicly disclosed escalation matrix. These requirements position the PA as the primary accountability point for payment-related disputes.

3. Technology, Security & Fraud Prevention

Operational resilience forms a core compliance pillar. PAs must implement Board-approved information security policies, comply with data storage localisation requirements applicable to payment system operators, and adhere to security standards such as PCI-DSS and PCI-SSF. Annual system and cyber-security audits by CERT-In empanelled auditors are mandatory, alongside ongoing compliance with RBI’s cyber resilience directions for non-bank payment system operators. Baseline technology recommendations set out in Annexure 1 of the PA Master Directions further reinforce this framework.

4. Regulatory Asymmetry for Payment Gateways

By contrast, “Payment Gateways” are not subject to these governance and conduct mandates, reflecting their exclusion from funds handling. Their regulatory exposure arises indirectly—through outsourcing norms, contractual obligations with regulated PAs and banks, and RBI-recommended (but non-mandatory) technology standards, reinforcing the asymmetric compliance burden between PAs and PGs.

KYC & Merchant Due Diligence – Who Bears the Compliance Load?

The RBI’s approach to KYC and merchant due diligence mirrors its broader regulatory philosophy: compliance responsibility follows settlement risk. Since “Payment Aggregators” intermediate and settle customer funds, they are designated as the primary gatekeepers for merchant onboarding and ongoing monitoring. Accordingly, the PA Master Directions place merchant-level KYC obligations squarely on PAs, aligned with the RBI’s Master Direction on Know Your Customer (KYC).

1. Core Due Diligence Obligations of Payment Aggregators

Every PA is required to undertake Customer Due Diligence (“CDD”) of its merchants at the time of onboarding. This includes retrieving and verifying KYC records from the Central KYC Records Registry (CKYCR), conducting background and antecedent checks, validating business profiles, and ensuring appropriate merchant identification and categorisation. Beyond onboarding, PAs must continuously monitor merchant transactions to ensure consistency with the merchant’s stated business activities and risk profile.

2. Proportionality and Assisted Due Diligence

Recognising operational realities, the PA Master Directions permit simplified onboarding for small merchants and low-value exporters below prescribed turnover thresholds. In such cases, alternative measures, such as PAN verification, Contact Point Verification (CPV), and verification of Officially Valid Documents, may be adopted. PAs may also utilise agents for assisted digital KYC and video-based customer identification procedures. However, the ultimate responsibility for compliance remains with the PA, irrespective of delegation.

3. Role of Acquiring Banks and Delegation Limits

Acquiring banks are not required to independently conduct merchant KYC where merchants are onboarded through an authorised PA, but must retain the ability to access KYC information and ensure alignment with their merchant acquisition policies. Where onboarding is routed through another PA or an overseas intermediary, regulatory responsibility continues to rest with the contracting PA.

4. Payment Gateways: No Direct KYC Burden

“Payment Gateways” bear no direct merchant KYC obligations under the PA Master Directions, reflecting their exclusion from funds handling. Their exposure is limited to contractual and outsourcing-related compliance, reinforcing the asymmetric allocation of KYC responsibility in the payments ecosystem.

Escrow, Settlement & Cross-Border Complexity

The RBI’s insistence on escrow arrangements for “Payment Aggregators” reflects its core concern with safeguarding customer and merchant funds against commingling, misuse, and settlement delays. Under the PA Master Directions, escrow accounts function as ring-fenced repositories for funds collected on behalf of merchants, distinct from the operational accounts of the PA. This structural separation is intended to reduce settlement risk and enhance traceability and supervisory oversight.

1. Domestic Escrow and Settlement Discipline

Non-bank PAs are mandatorily required to maintain escrow accounts with Scheduled Commercial Banks in India. These accounts may be used only for permitted credits and debits, including receipt of customer payments, settlement to onboarded merchants, refunds, chargebacks, and payment of PA commissions. Importantly, escrow balances cannot be used for any business other than authorised PA activity, and settlement timelines must be transparently documented in PA–merchant agreements, ensuring fairness and predictability.

2. The “Core Portion” and Interest Restrictions

The PA Master Directions introduce the concept of a “core portion” of the escrow balance—computed based on historical lowest balances, which may earn limited interest subject to strict conditions. No lien, loan, or encumbrance may be created over this amount, and banks are prohibited from issuing instruments that could confer proprietary rights over escrow balances. Periodic auditor certification of escrow compliance is mandatory, reinforcing regulatory discipline.

3. Cross-Border Payment Aggregation: Layered Complexity

For “PA – Cross Border” entities, escrow regulation operates alongside FEMA compliance. Separate Inward Collection Accounts (InCA) and Outward Collection Accounts (OCA) must be maintained, with an absolute prohibition on commingling or netting of inward and outward flows. Cross-border transactions are subject to a per-transaction cap of ₹25 lakh and must be routed exclusively through Authorised Dealer banks, adding a distinct compliance layer to settlement operations.

4. Payment Gateways: Structural Exclusion

“Payment Gateways” are excluded from escrow and settlement obligations under the PA Master Directions, consistent with their non-custodial role. Their regulatory exposure remains indirect, arising only through contractual arrangements and outsourcing norms, further underscoring escrow as a defining feature of PA regulation.

Reporting, Supervision & Ongoing RBI Oversight

Under the PA Master Directions, regulatory oversight of “Payment Aggregators” does not conclude with the grant of authorisation. Instead, authorisation operates as a continuing licence, conditioned on ongoing compliance and supervisory visibility. Reporting obligations function as the RBI’s primary tool to monitor settlement risk, financial soundness, governance discipline, and systemic stability within the payments ecosystem.

1. Reporting Obligations and Supervisory Architecture

Authorised PAs are subject to a structured and periodic reporting framework. This includes annual submissions such as audited financial statements, net-worth certificates, and system and cyber-security audit reports; quarterly certifications confirming escrow balance maintenance and permissible debits and credits; and monthly transaction statistics capturing volumes and values processed. In addition, event-based disclosures, including changes in board composition or management, must be promptly reported to the RBI.

This reporting architecture is reinforced through multiple gatekeepers. Statutory auditors certify financial and escrow compliance, banks monitor escrow operations and settlement discipline, and CERT-In empanelled auditors validate technology and cyber resilience. Together, these layers create a system of indirect but continuous supervision.

2. Supervisory Powers and Regulatory Asymmetry

The RBI retains broad powers to seek information, conduct inspections, issue directions, and impose corrective measures, including restrictions on operations or cancellation of authorisation in cases of persistent non-compliance. Reporting, therefore, operates as a preventive mechanism rather than a purely enforcement-driven tool.

By contrast, “Payment Gateways” are not subject to direct reporting or supervisory obligations under the PA Master Directions, reflecting their exclusion from funds handling. Their regulatory exposure remains indirect, mediated through banks, regulated PAs, and outsourcing arrangements, once again underscoring the asymmetric regulatory treatment based on custody of funds.

[1] https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/141MD7D7F25DEBF1F48449E20D685E4B014E5.PDF