In the Indian startup ecosystem, Software-as-a-Service (“SaaS”) subscription agreements are frequently treated as “industry standard” documents, downloaded, lightly modified, and deployed with minimal structural scrutiny. Founders often rely on templates sourced from US or European precedents, competitor websites, or investor-provided formats. While commercially convenient, this approach creates a fundamental misalignment: the agreement appears familiar, yet it may be legally incompatible with the company’s business model, infrastructure architecture, and regulatory exposure in India.

A SaaS subscription agreement does not operate in a vacuum. It is governed by the principles of risk allocation and damages under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, licence and assignment mechanics under the Copyright Act, 1957, enforceability of electronic contracts under the Information Technology Act, 2000, and increasingly, data governance obligations under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023. Each of these statutes materially affects how core clauses, particularly those relating to intellectual property, liability, and data processing, must be structured.

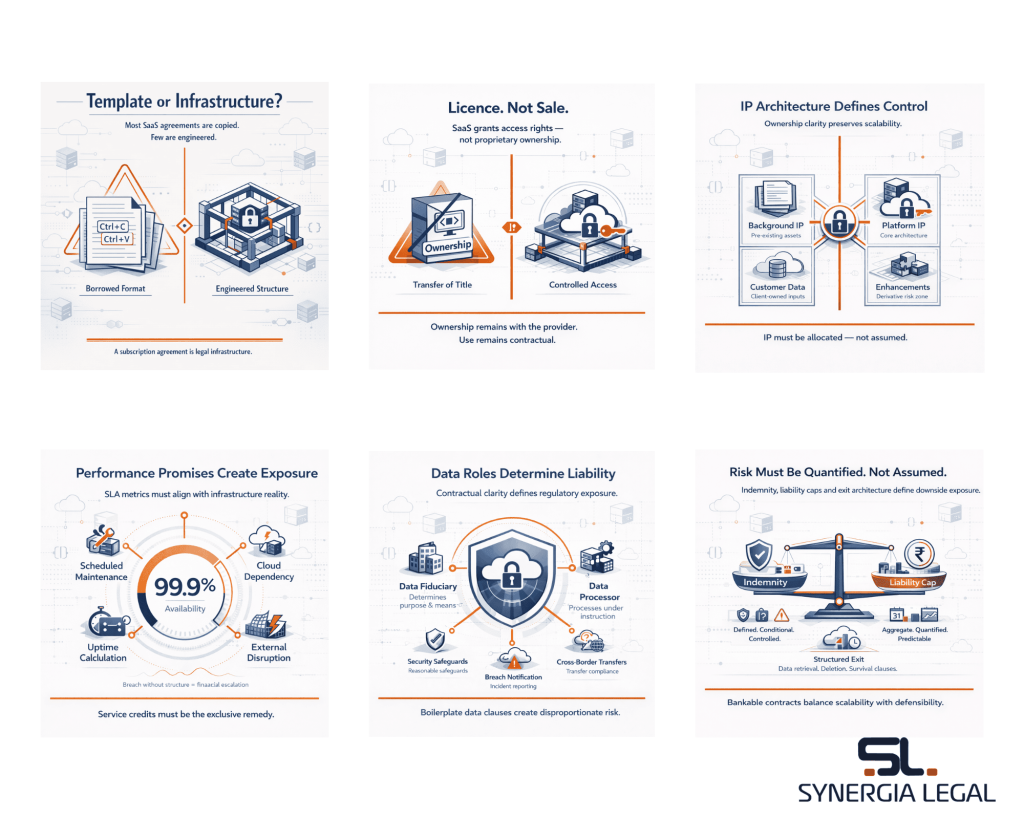

The misconception lies in assuming that “boilerplate” clauses are commercially neutral. In practice, these provisions determine the allocation of intellectual property rights, regulatory accountability, indemnity exposure, and termination leverage. Most SaaS disputes do not arise from pricing disagreements; they arise from poorly calibrated contractual architecture. A subscription agreement, therefore, is not merely a commercial instrument — it is the legal infrastructure upon which the product scales.

The Legal Character of SaaS: Licence, Access & Control

At its core, a SaaS transaction is not a sale of software. The customer does not acquire ownership of the underlying code, nor does it receive possession of a copy capable of independent exploitation. Instead, the commercial arrangement is structured as a limited, revocable right to access and use software hosted and controlled by the service provider. What is granted is contractual permission and not proprietary entitlement.

Under the Copyright Act, 1957, the distinction between an assignment and a licence is legally significant. An assignment transfers ownership rights in the work, whereas a licence merely authorises specified uses while ownership remains with the copyright holder. In the SaaS context, the service provider’s economic model depends upon retaining ownership of the platform and granting narrowly tailored usage rights. Ambiguously drafted “grant” clauses, particularly those using terms such as “perpetual,” “irrevocable,” or “exclusive” without qualification, risk blurring this distinction and expanding user rights beyond commercial intent.

The legal characterisation of SaaS as a licence arrangement has practical consequences. It informs the structuring of intellectual property clauses, determines the scope of termination and suspension rights, shapes indemnity exposure, and influences investor diligence on asset ownership. In SaaS, access is commercial, but control is contractual. The subscription agreement must therefore be drafted to preserve that control with precision and clarity.

Intellectual Property Architecture: Licence Grants, Ownership & Customisation

1. The Grant of License: Defining the Boundary of Use

The grant of licence clause is the structural foundation of any SaaS subscription agreement. Yet, many startups dilute their own intellectual property position by employing expansive and imprecise language, describing the licence as “perpetual,” “irrevocable,” or “unrestricted” without qualification. In a hosted SaaS model, the commercial intent is typically to provide a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and use the platform during the subscription term. Failure to clearly restrict sub-licensing, reverse engineering, unauthorised user access, or territorial scope may inadvertently broaden the customer’s rights beyond the provider’s intended risk profile.

Under the Copyright Act, 1957, the distinction between a licence and an assignment is legally significant. While SaaS transactions are intended to operate as licences, ambiguous drafting may invite arguments of expanded or implied rights. The licence clause must therefore articulate, with precision, that ownership of the software and all associated intellectual property remains vested in the service provider.

2. Ownership Architecture: Background IP, Platform IP & Client Data

A recurring drafting weakness lies in the failure to distinguish between different categories of intellectual property. Startups often neglect to clearly separate: (i) pre-existing or “Background IP”; (ii) core platform IP; (iii) customer data; and (iv) configurations or workflows created by the customer within the platform. Enterprise clients may seek “ownership of deliverables” or “ownership of improvements,” language that, if accepted without qualification, risks encumbering the provider’s ability to evolve its product.

A well-structured agreement must expressly retain ownership of Background IP and platform enhancements, while clarifying that customer data remains the property of the customer, subject to defined usage rights for service provision, analytics, and aggregated or anonymised insights.

3. Customisation & Enhancements: Managing Derivative Risk

Custom development and enterprise-specific integrations present particular risk. Where bespoke features are built, the agreement must clearly allocate ownership of such “Foreground IP” and address whether those enhancements may be integrated into the core platform. Absent careful drafting, including licence-back provisions and feedback clauses, startups risk fragmenting their own product architecture and undermining long-term scalability.

Service Commitments & Performance Risk: SLAs, Warranties & Suspension

1. Service Levels: Commercial Assurance vs Legal Exposure

Service Level Agreements (SLAs) are often drafted as competitive differentiators rather than calibrated risk instruments. Early-stage SaaS providers frequently commit to uptime metrics such as 99.9% or 99.99% availability without aligning those commitments with their actual infrastructure architecture. In many cases, the agreement omits necessary carve-outs for scheduled maintenance, force majeure events, third-party cloud outages, internet disruptions, or dependencies on external service providers. Equally problematic is the absence of clarity on how uptime is calculated, including measurement intervals, exclusions, and reporting methodology.

An imprecisely drafted SLA may convert routine technical interruptions into contractual breach claims. Without defined limitations and structured remedies, service commitments risk escalating into disproportionate damages exposure and enterprise negotiation pressure.

2. Warranties: Absolute Promises vs Qualified Commitments

Warranty clauses present similar risks. Language suggesting that services will be “error-free,” “uninterrupted,” or “fit for all purposes” creates absolute obligations that are commercially unrealistic in a cloud-based environment. In the absence of carefully drafted disclaimers, such warranties may expand exposure under Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, which governs compensation for breach.

A defensible SaaS agreement typically limits warranties to material conformity with documentation, excludes implied warranties to the extent permissible under law, and avoids performance guarantees that cannot be technically sustained.

3. Remedies & Suspension: Containing Downside Risk

The remedial framework must contain, rather than amplify, performance risk. Service credits should be clearly structured as the sole and exclusive remedy for SLA breaches, subject to defined caps. Cure periods and structured escalation mechanisms further reduce litigation risk. Equally important is the provider’s right to suspend services in cases of non-payment, security threats, or regulatory exposure. SLA architecture, when properly designed, allocates performance risk proportionately and preserves operational contro.

Data Governance & Regulatory Exposure: DPDP Compliance in SaaS

1. Regulatory Recalibration: Data Clauses Are No Longer Boilerplate

The enactment of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“DPDP Act”) has materially altered the risk landscape for SaaS providers operating in India. Data protection provisions in subscription agreements can no longer be treated as template insertions. The DPDP Act imposes statutory obligations on “Data Fiduciaries” in relation to lawful processing[1], notice requirements[2], consent[3], and implementation of reasonable security safeguards[4]. In enterprise SaaS arrangements, contractual allocation of data roles directly influences regulatory accountability and potential exposure.

2. Role Allocation: Data Fiduciary vs Data Processor

A recurring drafting weakness lies in the failure to clearly define the respective roles of the parties. In many SaaS models, the enterprise customer qualifies as the “Data Fiduciary,” determining the purpose and means of processing, while the SaaS provider operates as a “Data Processor” acting on documented instructions. The DPDP Act recognises processing through a Data Processor under contract[5], yet primary compliance obligations, including responding to Data Principal rights[6], remain with the Data Fiduciary.

Where agreements blur this distinction or impose fiduciary-level obligations on the provider without qualification, startups risk assuming disproportionate liability. Proper drafting should expressly identify role allocation, restrict processing to documented instructions, and require sub-processors to be engaged under appropriate contractual safeguards.

3. Security, Incident Response & Cross-Border Transfers

Section 8(5) of the DPDP Act requires implementation of reasonable security safeguards to prevent personal data breaches. Subscription agreements must therefore articulate calibrated security commitments, avoiding vague references to “industry standard” practices without definition. Equally important are structured breach notification timelines, recognising that statutory reporting obligations may be triggered by the Data Protection Board.

Cross-border transfers are permitted except to restricted territories notified by the Central Government[7]. Accordingly, agreements should transparently disclose hosting locations and address transfer mechanics. Data retention and deletion obligations must also be aligned with statutory principles of purpose limitation.

In SaaS contracting, data architecture defines regulatory exposure, and contractual clarity determines accountability.

Indemnities & Liability Caps: The Economics of Risk

1. Indemnities: Targeted Protection or Open-Ended Exposure?

Indemnity clauses in SaaS subscription agreements are frequently negotiated as headline risk provisions. Typically, service providers agree to indemnify customers against third-party claims arising from intellectual property infringement, data breaches, or violation of applicable law. However, startups often accept overly expansive language, indemnifying against “any and all claims” connected, directly or indirectly, with the services, without qualification or limitation.

Such drafting can convert a contractual dispute into immediate third-party liability exposure. In the absence of knowledge qualifiers, exclusions for customer misuse, unauthorised modifications, or integration with non-approved third-party systems, the indemnity becomes structurally unmanageable. A well-calibrated indemnity must be specific to defined risks, subject to conditions, and aligned with the provider’s actual operational control. Indemnities are not intended to function as blanket insurance policies; they are risk allocation mechanisms for clearly identified contingencies.

2. Defence Control & Procedural Mechanics

Equally critical, though often overlooked, are procedural safeguards. The agreement must specify prompt notice requirements, the indemnifying party’s right to control the defence, and restrictions on settlement without written consent. Absent these controls, the indemnified party may settle claims imprudently or expand liability exposure without operational oversight. Indemnity clauses must therefore integrate substantive protection with procedural discipline.

3. Limitation of Liability: Calibrating the Financial Ceiling

Limitation of liability clauses operate as economic stabilisers within the contract. Common drafting errors include linking the liability cap to the total contract value rather than fees paid in a defined period, failing to provide an aggregate cap, or carving out multiple categories, such as intellectual property, confidentiality, and data protection, in a manner that effectively nullifies the cap.

Under Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, damages are compensatory in nature, and Indian courts have generally upheld commercially negotiated caps, provided they are not unconscionable or contrary to public policy under Section 23. A rational approach may include an aggregate cap linked to annual subscription fees, tiered caps for specific high-risk categories, and express exclusion of indirect or consequential damages.

Ultimately, liability architecture is not about eliminating risk; it is about quantifying and allocating it in proportion to commercial consideration and operational control.

Term, Termination & Exit Mechanics

1. Term & Renewal: Revenue Certainty vs Contractual Ambiguity

The term clause in a SaaS subscription agreement defines the commercial rhythm of the relationship. Whether structured as a fixed-term contract with auto-renewal or a rolling subscription model, clarity is essential. Ambiguities in renewal mechanics — particularly notice periods, pricing upon renewal, and method of termination — frequently give rise to disputes. Startups often rely on generic auto-renewal language without specifying the timeline or manner in which either party may opt out. Such drafting weakens revenue predictability and may expose the provider to allegations of unfair termination or unilateral pricing changes. A well-drafted renewal framework must clearly articulate duration, notice thresholds, and applicable renewal pricing principles.

2. Termination Rights: Cure, Convenience & Cause

Termination provisions determine contractual leverage. Immediate termination rights without cure periods may appear protective but can be commercially destabilising. Conversely, overbroad termination for convenience clauses — particularly those exercisable without notice, undermine revenue certainty and enterprise trust. The agreement should define “material breach,” provide reasonable cure periods, and distinguish between suspension and termination. Suspension rights, especially in cases of non-payment, security threats, or regulatory risk, preserve operational control without prematurely extinguishing the contract. Structured termination provisions reduce litigation risk and align exit triggers with genuine contractual non-performance.

3. Exit Architecture: Data & Post-Termination Control

The true stress test of a SaaS agreement arises at exit. Subscription agreements must address customer data retrieval windows, deletion timelines, and the scope of any transition assistance. Survival clauses should preserve intellectual property protections, confidentiality, and agreed liability limitations. Absent a clearly defined exit architecture, disputes over data access and continued use can expose the provider to both commercial and regulatory risk.

Governing Law, Dispute Resolution & Enforceability

1. The Template Problem: Imported Governing Law Clauses

A recurring drafting anomaly in Indian SaaS subscription agreements is the adoption of foreign governing law clauses, typically Delaware, New York, or English law, borrowed from investor templates or global enterprise precedents. While commercially familiar, such clauses often bear little connection to the operational realities of an Indian-incorporated entity servicing Indian customers. Where assets, management, and contractual performance are primarily located in India, the selection of foreign law may complicate enforcement, increase litigation costs, and create jurisdictional ambiguity. Governing law should reflect commercial nexus, not aspirational branding.

2. Arbitration Architecture: Seat, Venue & Interim Relief

Even where arbitration is selected as the dispute resolution mechanism, structural precision is critical. Under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, the juridical “seat” determines supervisory jurisdiction and procedural law. Confusion between seat and venue can create enforceability uncertainty. Agreements should clearly specify the seat, governing law of the contract, and procedural framework. Consideration must also be given to interim relief mechanisms, including recourse to courts under Section 9 of the Act. Poorly drafted arbitration clauses risk prolonged jurisdictional disputes before substantive issues are even addressed.

Ultimately, dispute resolution clauses are not drafted for optimism but for enforceability. A well-calibrated governing law and arbitration framework reduces uncertainty, strengthens negotiation posture, and ensures that contractual rights remain practically executable.

Strategic Takeaways: From Template to Bankable Contract

A SaaS subscription agreement should be viewed not as a standardised legal document, but as a form of operational infrastructure. It reflects how a company allocates risk, protects its intellectual property, structures its data governance, and safeguards revenue continuity. The alignment between product architecture, hosting model, customer segment, and contractual terms is a marker of institutional maturity. Where agreements are copied without recalibration, contractual language may contradict commercial intent and create avoidable exposure.

Enterprise customers increasingly subject SaaS contracts to rigorous scrutiny, particularly in relation to data protection compliance, service level commitments, indemnity exposure, and liability caps. The enactment of the DPDP Act has heightened this sensitivity. Equally, investors conducting diligence routinely examine subscription agreements for structural red flags, including ambiguous ownership provisions, uncapped indemnities, disproportionate liability carve-outs, and unclear termination mechanics. These deficiencies do not merely create legal risk; they impair valuation and delay deal execution. At the same time, over-defensive drafting may impede enterprise adoption. Liability caps that are commercially unrealistic or refusal to assume calibrated indemnity obligations can stall negotiations and undermine credibility. The objective is not maximal protection, but rational allocation. A well-structured SaaS agreement balances scalability with defensibility, enabling growth without compromising structural control. In this sense, the transition from template to bankable contract is not cosmetic, it is strategic.

[1] Section 4 of the DPDP Act

[2] Section 5 of the DPDP Act

[3] Section 6 of the DPDP Act

[4] Section 8 of the DPDP Act

[5] Section 8(2) of the DPDP Act

[6] Sections 11–14 of the DPDP Act

[7] Section 16 of the DPDP Act