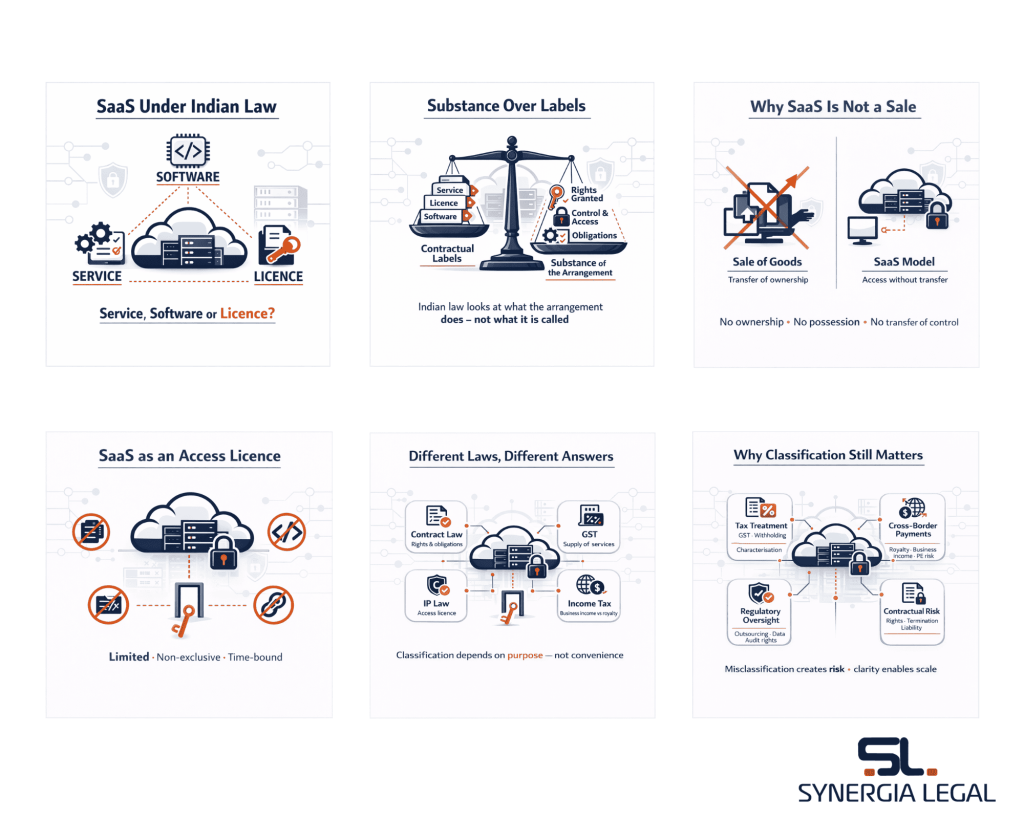

Software-as-a-Service (“SaaS”) has achieved near-universal commercial acceptance as a dominant software delivery model. In market practice, SaaS offerings are routinely described, and often contractually labelled, as the provision of “services”. This shorthand, while convenient, creates an illusion of legal certainty that Indian law does not fully support. Unlike several mature digital jurisdictions, Indian law does not recognise SaaS as a distinct legal category. Instead, its treatment remains fragmented across contract law, tax statutes, intellectual property law, exchange control regulations and sector-specific regulatory frameworks.

The question of whether SaaS constitutes a service, software, or a licence is therefore not merely semantic. Classification directly affects tax incidence and withholding obligations, characterisation of cross-border payments, determination of intellectual property rights, applicability of regulatory outsourcing norms, and enforceability of contractual risk allocation. Indian courts and regulators have consistently demonstrated reluctance to accept contractual labels at face value, preferring to examine the substance of rights conferred and obligations assumed. This “substance over form” approach is particularly evident in judicial treatment of software and technology transactions, where the distinction between transfer of goods, provision of services and grant of limited rights has been central to legal outcomes.[1]

SaaS further complicates traditional classification because it is neither a pure service nor a conventional software licence. Typical SaaS arrangements involve a composite bundle of obligations, continuous hosting, remote access, functional enablement, periodic updates and data processing, without any transfer of possession or ownership of software. Treating such arrangements as falling neatly within a single legal bucket risks regulatory misalignment and compliance exposure.

This article adopts a transaction-specific, consequence-driven approach to SaaS classification under Indian law, analysing how different legal regimes characterise the same arrangement for distinct purposes, and why that divergence continues to matter.

Understanding SaaS Through a Legal Lens

Legal characterisation of SaaS requires moving away from infrastructure-centric or technological descriptions, such as cloud architecture, servers or application layers, and focusing instead on the nature of rights conferred and obligations assumed by the parties. Indian courts and regulators have repeatedly emphasised that the legal nature of a transaction must be determined by its substance and economic reality, rather than by the mode of delivery or contractual labels attached to it.

From a legal perspective, a typical SaaS arrangement is defined by a set of core attributes. First, the customer does not receive possession or ownership of any software or executable code; access to functionality remains entirely remote and centrally controlled by the provider. Second, the rights granted are limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable and time-bound, terminating automatically upon expiry or termination of the agreement. Third, the customer is contractually restricted from reproducing, modifying, sublicensing or commercially exploiting the underlying software, reinforcing the absence of any transfer of proprietary rights.

Correspondingly, the SaaS provider assumes continuous and performance-oriented obligations, including hosting, availability, maintenance, updates, security and data processing. The value of the transaction is therefore not derived from delivery of a product, but from ongoing performance over the term of the contract. Termination does not involve return of goods or reversal of a transfer, but merely cessation of access.

These attributes position SaaS as a composite and continuing legal arrangement, resisting binary classification as either a sale of goods or a conventional software licence. Indian law, consequently, demands a transaction-specific analysis that examines the functional allocation of rights, control and risk, rather than relying on simplified categorisations driven by commercial practice or tax treatment alone.[2]

SaaS Under Indian Private Law: Service, Sale, or Licence?

The private law characterisation of SaaS must be examined against the foundational principles of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 and, where relevant, the Sale of Goods Act, 1930. Indian courts have consistently held that the legal nature of a transaction depends on the substance of the rights and obligations created, rather than the terminology adopted by the parties.[3]

As a starting point, SaaS does not comfortably fall within the concept of a “sale of goods”. A sale under the Sale of Goods Act presupposes a transfer of property in goods from the seller to the buyer for a price. In a typical SaaS arrangement, there is no transfer of ownership, possession or dominion over software or any tangible or intangible good. The customer neither receives deliverable software nor acquires the right to dispose of it. Indian courts have cautioned against extending sale principles to arrangements where control and ownership remain with the supplier.[4]

SaaS also exhibits features of a contract for services, particularly due to the provider’s continuous obligations relating to hosting, maintenance, updates and availability. However, a pure service classification is incomplete. The customer’s rights are not limited to effort-based performance but include a controlled right to access and use proprietary software functionality, subject to contractual and technical restrictions.

This brings SaaS closer to the concept of a licence under Indian law, a permission to do something which would otherwise be unlawful, without creating any proprietary interest. SaaS arrangements typically grant a limited, non-exclusive and non-transferable right to access software, without any right to exploit the underlying intellectual property. Importantly, such licences differ from traditional software licences, as they do not involve delivery of a copy of the software.[5]

Viewed holistically, SaaS emerges as a composite private law arrangement. Indian jurisprudence favours a dominant purpose and substance-over-form analysis, recognising that SaaS cannot be reduced to a single classical category without distorting its legal and commercial reality.

SaaS, Software and “Goods”: Judicial Evolution Under Indirect Tax Laws

Indian courts were first required to grapple with the taxability of software under the pre-GST sales tax and value added tax regimes, in the absence of clear statutory guidance. The central inquiry consistently focused on the nature of the supply, whether the transaction involved a transfer of property or merely facilitated use. This led to a jurisprudence that examined software not as a monolithic category, but through the lens of how it was supplied and controlled.

1. Distinction Between Forms of Software Supply

Judicial reasoning gradually evolved to distinguish between three broad forms of software supply. Off-the-shelf or packaged software, being standardised and capable of commercial circulation, was more readily classified as goods where it could be delivered and transferred for consideration. Customised software, developed to meet the specific needs of a customer, occupied an intermediate position, with courts examining whether the dominant element of the transaction was development service or supply of a usable product. In contrast, online or hosted software access, where no copy of the software is delivered and operational control remains with the supplier, was treated as fundamentally distinct.

2. Limits of Treating Software as “Goods”

The Supreme Court clarified that classification as goods depends not merely on marketability, but on whether there is a transfer of the right to use software, requiring delivery of possession and effective control. Where customers only receive access, without the ability to deploy, reproduce or commercially exploit the software, the essential conditions for treating the transaction as a sale or deemed sale are not satisfied[6].

3. Application of Judicial Principles to SaaS

SaaS aligns squarely with the category of online or hosted software access. SaaS models involve no delivery of software, no transfer of possession, and no vesting of effective control in the customer. Ownership, deployment rights and technical control remain with the provider throughout the arrangement, rendering the traditional goods-based analysis inapplicable.

4. Statutory Re-Orientation Under GST

The Goods and Services Tax regime reflects this functional distinction. Under the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 and the Integrated Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, SaaS is ordinarily treated as a supply of services, including, in cross-border scenarios, as Online Information and Database Access or Retrieval Services (OIDAR). However, GST classification is tax-specific and does not conclusively determine the private law or regulatory character of SaaS.

While GST has simplified indirect tax administration, it has not erased the legal distinctions developed in earlier jurisprudence. The judicial differentiation between packaged software, customised software and hosted access continues to inform how SaaS is understood—underscoring that access-driven, centrally controlled models remain legally distinct from software supplied as goods.

Intellectual Property Perspective: SaaS as an Access Licence

Under Indian intellectual property law, computer programmes are expressly recognised as “literary works” under the Copyright Act, 1957, vesting the copyright owner with a bundle of exclusive rights, including the rights of reproduction, adaptation, issuance of copies and communication to the public. Any lawful use of software by a third party must therefore be traced to either an assignment of copyright or a licence permitting limited use of such rights.

The Copyright Act, 1957 draws a clear doctrinal distinction between an assignment and a licence. An assignment entails a transfer of ownership in one or more exclusive rights, whereas a licence merely confers a permission to do something which, absent such permission, would amount to infringement. Critically, a licence does not create any proprietary interest in the copyright itself and must be construed narrowly, having regard to the scope of rights actually parted with by the copyright owner.

When examined through this lens, typical SaaS arrangements align more closely with an access-based licence than with any transfer or licensing of copyright. SaaS customers are generally granted a limited, non-exclusive, non-transferable and revocable right to access software functionality hosted and controlled by the provider. They are contractually prohibited from reproducing, modifying, distributing, sublicensing or otherwise exploiting the underlying software, whether in source or object code form. The provider retains complete ownership, control and deployment rights at all times.

Judicial treatment of software under Indian copyright law further reinforces this distinction. In Microsoft Corporation v. Yogesh Papat[7], the Delhi High Court held that use of software beyond the scope of the licence granted by the copyright owner constitutes infringement, underscoring that user rights are strictly limited to the permissions expressly conferred. The Court’s reasoning affirms that access to software functionality does not dilute the copyright owner’s exclusive control over reproduction, modification or commercial exploitation.

SaaS arrangements, which involve no delivery of software copies and no vesting of exploitative rights, therefore operate as permissions to access functionality rather than as traditional software licences. This access-centric character has direct implications for IP ownership, infringement analysis, termination consequences and downstream contractual risk allocation.

Cross-Border SaaS Payments: Royalty, Service Fee or Business Income?

The classification of cross-border payments for SaaS assumes critical significance under Indian tax law, as it directly impacts withholding obligations, treaty eligibility and exposure to interest and penalties. Indian tax authorities have historically sought to characterise software and technology-related payments as “royalty” or, alternatively, as fees for technical services (“FTS”), often leading to disputes where commercial arrangements are access-based and automated in nature.

Under the Income-tax Act, 1961, royalty is defined to include consideration for the transfer of, or the right to use, any copyright in a literary work, including computer software. Judicial interpretation has consistently drawn a distinction between the use of copyright and the use of a copyrighted article. Where a payer merely accesses software functionality without acquiring rights to reproduce, modify, adapt or commercially exploit the software, the payment does not constitute royalty. This principle has been reaffirmed in multiple decisions culminating in the Supreme Court’s clarification that payments for access to standard software, without parting of copyright rights, fall outside the scope of royalty.

Attempts to characterise SaaS payments as FTS have also been judicially constrained. Courts and tribunals have consistently held that FTS requires the rendering of managerial, technical or consultancy services involving human intervention. In DCIT v. Savvis Communication Corporation[8], and Salesforce.com Singapore Pte Ltd. v. DCIT[9],, automated, standardised cloud-based services were held not to constitute FTS or royalty, as the services were delivered through an automated platform without human involvement.

In this backdrop, SaaS consideration is increasingly viewed as business income of the non-resident provider. Where the SaaS provider does not have a permanent establishment in India, such income is generally not taxable in India under applicable Double Taxation Avoidance Agreements. However, inconsistent contractual drafting and loose characterisation of payments continue to create litigation risk. A disciplined alignment between IP characterisation, service delivery model and tax positioning therefore remains essential for cross-border SaaS structures.

Regulatory Expectations: Why Labels Don’t Work for Regulators

Indian regulators have consistently adopted a functional, risk-based approach to technology arrangements, including SaaS, placing limited reliance on contractual labels such as “service”, “licence” or “software”. From a regulatory standpoint, the legal characterisation agreed between private parties is secondary to the actual role performed by the SaaSprovider, the degree of operational dependence created, and the risks introduced into the regulated entity’s business.

SaaS providers are increasingly viewed not as ordinary vendors, but as critical third-party technology dependencies. Regulatory scrutiny therefore focuses on questions of control, resilience and substitutability—who controls the system, where data is stored and processed, how continuity is ensured, and whether effective exit mechanisms exist. These concerns arise irrespective of whether the SaaS arrangement is framed as a service contract or an access licence, because regulatory risk is driven by functionality, not form.

Data protection and supervisory access further reinforce this approach. Regulators expect regulated entities to retain adequate oversight over data flows, security controls and incident response mechanisms, and to ensure audit and inspection rights over outsourced technology functions. SaaS models that centralise hosting and operational control with the provider attract heightened scrutiny, particularly where the service underpins core business processes.

This functional approach is evident across regulated sectors, including financial services, payments, insurance and healthtech, where SaaS providers are frequently brought within outsourcing, third-party risk management and technology governance frameworks. In this context, reliance on contractual labelling alone often leads to regulatory misalignment—where agreements appear compliant on paper but fail to address operational and supervisory expectations.

Contract Structuring Implications: Drafting for Classification Discipline

SaaS agreements are often the primary documentary basis on which courts, tax authorities and regulators assess the legal character of a transaction. Inconsistent or imprecise drafting—particularly where commercial terminology is borrowed from software licensing or sale arrangements—frequently leads to adverse inferences. Contracts must therefore reflect, with discipline, the access-based and performance-oriented nature of SaaS models.

1. Structuring the Grant of Rights

The grant clause should be carefully framed as a limited right to access and use functionality, rather than as a transfer or licence of software. Language implying delivery, possession or ownership of software should be avoided. Rights should be expressly non-exclusive, non-transferable, revocable and restricted to the term and permitted purposes of the agreement, reinforcing the absence of any proprietary interest.

2. Aligning Intellectual Property Provisions

IP clauses should unambiguously vest ownership of all underlying software and platform IP with the provider. User rights should be narrowly scoped, with explicit prohibitions on reproduction, modification, sublicensing or reverse engineering. Treatment of derivatives, feedback and usage data should be addressed to prevent unintended expansion of user rights through implication.

3. Payment, Tax and Characterisation Consistency

Consideration clauses should be aligned with the intended classification of the transaction. Royalty-style language and references to “licence fees” should be avoided where no copyright rights are transferred. Withholding tax, gross-up and indemnity provisions should be calibrated to the access-based nature of SaaS payments to reduce future disputes.

4. Regulatory and Data Readiness

Given heightened regulatory scrutiny of technology outsourcing, contracts should incorporate audit, inspection and compliance rights, along with clear data ownership, access and exit obligations. Termination provisions should contemplate cessation of access and orderly data transition, rather than return of assets, reinforcing the SaaS model as one of controlled access rather than transfer.

Why Classification Still Matters in India

Unlike several mature digital jurisdictions, Indian law does not recognise SaaS as a distinct legal category. Its treatment remains fragmented across contract law, tax statutes, intellectual property law, exchange control regulations and sectoral regulatory frameworks. As a result, the same SaaS arrangement may be characterised differently depending on the legal lens applied, creating uncertainty and compliance risk for both providers and customers.

1. Financial, Tax and Cross-Border Consequences

Classification directly impacts indirect tax treatment, withholding tax exposure and cross-border remittance permissibility. Mischaracterisation of SaaS payments as royalty or fees for technical services can trigger withholding obligations, interest and penalties, even where the commercial arrangement is access-based. From a foreign exchange perspective, inconsistent characterisation between contracts and remittance documentation often leads to enhanced banking scrutiny and transaction delays.

2. Regulatory and Supervisory Implications

For regulators, SaaS is increasingly viewed as a form of critical technology dependency rather than a routine commercial service. Classification influences the applicability of outsourcing norms, data governance requirements, audit rights and business continuity expectations, particularly in regulated sectors such as financial services, payments and healthtech. Labels adopted by contracting parties offer limited insulation where the functional role of the SaaS provider creates systemic or operational risk.

3. Contractual Enforcement and Dispute Exposure

Indian courts have repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to look beyond contractual labels to assess the substance of technology arrangements. Inconsistent drafting, where access-based models are framed using licence or sale terminology, can weaken enforcement positions and distort allocation of rights and liabilities during disputes.

4. Strategic Considerations for Indian SaaS Businesses

For founders and investors, classification discipline is not merely a compliance exercise but a strategic necessity. Clear and coherent legal characterisation supports scalable cross-border operations, reduces regulatory friction, strengthens diligence outcomes and aligns commercial growth with long-term legal resilience.

Practical Takeaways for SaaS Companies and Advisors

1. Treat Classification as a Legal Design Choice

For SaaS companies, classification should not be approached as a post-facto tax or compliance exercise. The legal character of a SaaS offering must be consciously designed at the product and contracting stage, with a clear understanding of how rights are granted, how services are delivered, and where control resides. Reliance on market shorthand—such as describing all SaaS as “services”—offers limited protection under Indian law.

2. Ensure Internal Consistency Across Legal Positions

One of the most common sources of risk in SaaS structures is inconsistency. Contracts may describe SaaS as a licence, tax positions may assume a service model, while regulatory frameworks treat the arrangement as a critical technology dependency. Such fragmentation invites scrutiny. SaaS companies and their advisors must align contractual drafting, tax characterisation and regulatory readiness around a coherent, access-based narrative grounded in substance rather than labels.

3. Adopt a Transaction-Specific and Jurisdiction-Aware Approach

There is no universal classification of SaaS under Indian law. Legal treatment varies depending on the statute, the purpose of analysis and the factual matrix of the transaction. This complexity is amplified in cross-border SaaS models, where treaty interpretation, foreign exchange regulations and local regulatory expectations intersect. Standardised global templates should therefore be carefully localised for Indian operations.

4. Periodically Revisit Legacy Arrangements

Many SaaS agreements currently in use were drafted before recent judicial and regulatory developments. Legacy language, particularly around licensing, royalties or technical services, can materially increase litigation and compliance risk. Periodic legal audits and selective re-papering are essential to ensure continued alignment.

5. Conclusion: Beyond Classification Labels

SaaS is, by design, a legally hybrid construct. Indian courts, regulators and tax authorities increasingly converge on a functional, substance-driven analysis that resists rigid categorisation. For SaaS companies and their advisors, the objective is not to force SaaS into a single legal bucket, but to design legally coherent structures that withstand scrutiny, enable scale and reflect economic reality.

[1] see Tata Consultancy Services v. State of Andhra Pradesh, (2005) 1 SCC 308; Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence (P) Ltd. v. CIT, (2021) 3 SCC 321

[2] see Engineering Analysis Centre of Excellence (P) Ltd. v. CIT, (2021) 3 SCC 321

[3] Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd. v. Union of India, (2006) 3 SCC 1

[4] Supra Note 1

[5] Supra Note 2

[6] Supra Note 1

[7] 2016 SCC OnLine Del 1430

[8] (2016) 76 taxmann.com 58 (ITAT Mum)

[9] (2022) 136 taxmann.com 354 (ITAT Del).